Ulnar Collateral Ligament

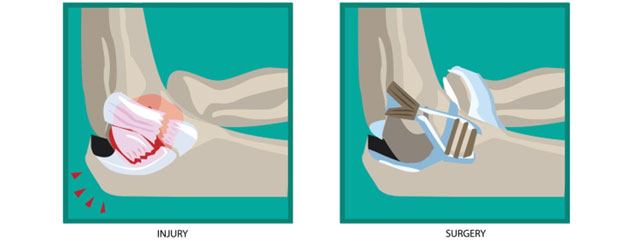

- Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction often referred to as “Tommy John Surgery” is a common procedure performed in throwing athletes

- The ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) is a thick band of tissue along the inside of the elbow that acts as the primary stabilizer to the elbow during the throwing motion

- The pitching motion consists of a sequential transfer of energy from the lower extremity to the arm and finally to the ball:

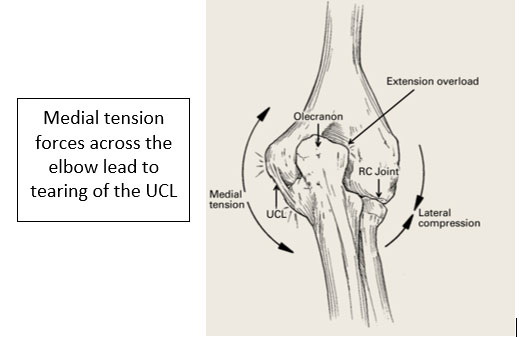

- During the throwing motion a significant amount of force is transferred across the elbow joint. The medial elbow will experience nearly 60 newton meters of torque and acceleration up to 2700 degrees/second during the throwing motion.

- Biomechanical studies have shown the UCL to fail around 34 newtons of force.

- Increased activation of forearm muscles combined with proper mechanics significantly decreases the load across the medial elbow therefore protecting the UCL from failure. However, the ligament still approaches its’ load to failure with each throw.

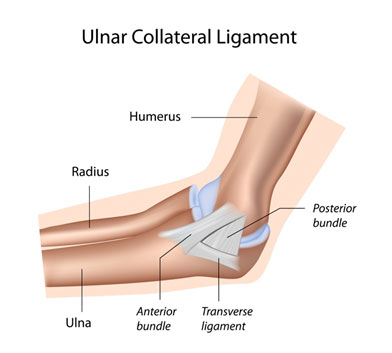

- The UCL originates off the medial epicondyle of the humerus and inserts on the sublime tubercle of the ulna 2.8 mm distal to the articular margin. It averages 26.7 mm in length and 4-5 mm in width and consists of 3 main components.

- Anterior Bundle

- Anterior Band (***primary ligament that is reconstructed at surgery)

- Posterior Band

- Posterior Bundle

- Transverse Ligament

- Anterior Bundle

- Overhead throwing athletes generate significant distraction forces across the inside of the elbow which leads to repetitive stress across the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and ultimately can lead to ligament failure

- UCL tears can occur following a single throw leading to a “pop” (acute tear) or because of repetitive throwing and accumulative forces over time that lead to degeneration of the ligament (chronic tear)

- Tommy John surgery consists of replacing the damaged ligament with a tendon from the forearm or hamstring. In some cases, the injured UCL can be repaired directly

- Recent studies have shown a dramatic increase in UCL injuries and reconstruction among high school and amateur pitchers

- Risk factors include:

- Exceeding youth baseball pitch counts

- High velocity throwers

- Poor mechanics including core weakness/ loss of shoulder motion

- Early sport specialization (Athlete less than 12 years old playing a single sport for at least 8 months per year)

- Risk factors include:

SYMPTOMS:

- UCL injuries can occur from a single acute injury or as a chronic overuse injury

- Acute injuries typically present with a “pop” followed by immediate pain and difficulty throwing

- Injuries can also occur due to repetitive microtrauma forces associated with the repetitive throwing motion which ultimately leads to attenuation and eventual degeneration and rupture of the UCL

- Throwing athletes with partial and complete UCL tears can present with a multitude of symptoms that may include:

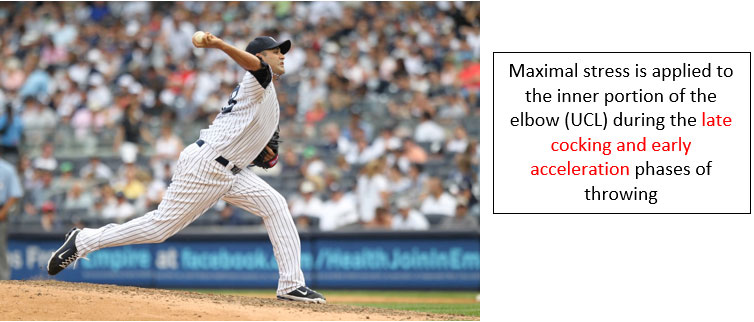

- Pain localized to the inside of the elbow. Most notable in the late cocking or early acceleration phase

- Stiffness or tightness within the elbow and forearm

- Numbness or tingling to the ring and small finger

- Difficulty warming up/getting loose, decreased velocity, difficulty with control/command

- Physical examination may demonstrate:

- Decreased range of motion with loss of both flexion or extension

- Swelling over the medial elbow

- Tenderness at the medial epicondyle, along the UCL or at the sublime tubercle

- Pain associated with moving valgus stress test

DIAGNOSIS:

- An athlete with a suspected UCL injury will undergo initial X-rays to look for any loose bodies, stress fractures, bone spurs or even avulsion fractures

- MRI is the study of choice to fully evaluate the UCL for potential injury

- In some cases, dye (MR Arthrogram) will be injected into the elbow to help identify subtle tears

- MRI can detect partial thickness tears, full thickness tears as well as muscle strains and stress fractures

- Full thickness tears, distal tears, partial tears with significant edema or chronic ligamentous changes have been shown to have less healing potential

- Stress radiographs and dynamic ultrasound can also help aid in the diagnosis of UCL injury

TREATMENT:

- There are many factors to consider when determining operative vs nonoperative treatment of UCL injuries. All of the following can influence treatment decision:

- Degree of UCL tear

- Chronicity of symptoms

- Season and career timing

- High-demand positions

NONOPERATIVE:

- Nonoperative treatment includes:

- Complete rest from throwing

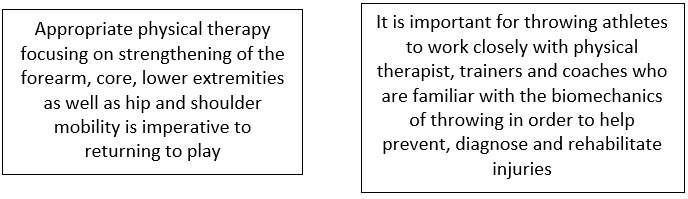

- Strengthening program focusing on forearm, shoulder, leg, hip and core

- Progressive throwing program focused on optimizing pitching mechanics

- NSAIDS and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) are also utilized in nonoperative management

- The forearm musculature helps stabilize and minimize forces across the UCL. The muscles can be strengthened through exercise, whereas the UCL cannot. Therefore, a primary emphasis of rehabilitation and prevention focuses on strengthening the forearm musculature surrounding the elbow. Muscle strains should also be fully recovered prior to returning to throwing to maximize their protective impact on the elbow and prevent subsequent ligamentous injury

OPERATIVE:

- Surgical intervention is reserved for high-level throwers who desire to compete and those who have previously failed nonoperative management

- Outcomes and return to sport following UCL reconstruction depend on precise anatomic recreation of the UCL and appropriate postoperative rehabilitation

- UCL reconstruction should only be performed by surgeons familiar with appropriate surgical technique and bone tunnel placement to ensure appropriate ligamentous reconstruction

- Postoperative therapy should only be under the direct care of a therapist who is familiar with postoperative UCL protocols and the specifics of progression through a throwing program

- There are multiple surgical techniques described to recreate the ulnar collateral ligament and studies have failed to define a single optimal technique. Therefore, the most important factor is surgeon comfort and experience with a particular technique.

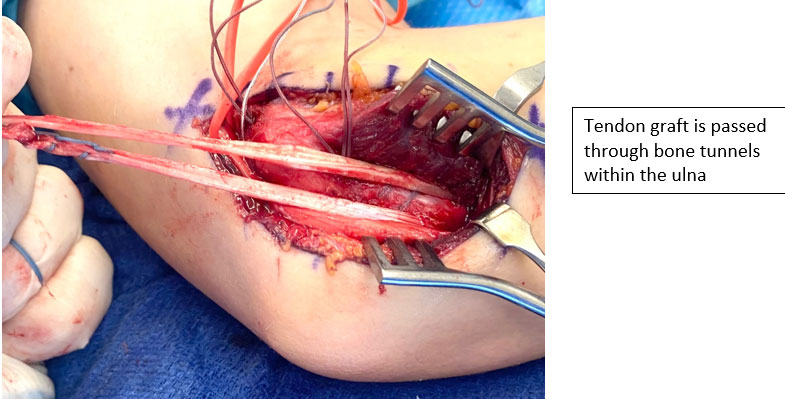

- In general, surgical techniques requires recreation of ulnar and humeral tunnels for placement of a tendon graft to reconstruct the ulnar collateral ligament

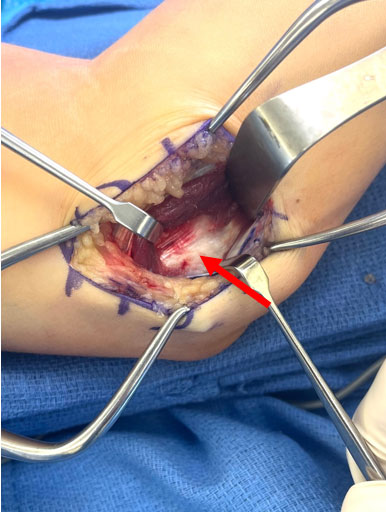

Proximal Ulnar Collateral Ligament reconstruction with chronic calcified ligamentous changes and bony fragments not amenable to repair and therefore requiring reconstruction

Palmaris Longus is a tendon that is commonly harvested from the forearm for graft usage. When a palmaris is not present (15-20%) a hamstring tendon can be utilized

Tendon graft is “docked” within the medial epicondyle to reconstruct the ulnar collateral ligament

UCL REPAIR:

- Return to play following UCL reconstruction is lengthy, typically 12-18 month recovery for pitchers. Ligament insufficiency from chronic pathology should always be treated with ligament reconstruction

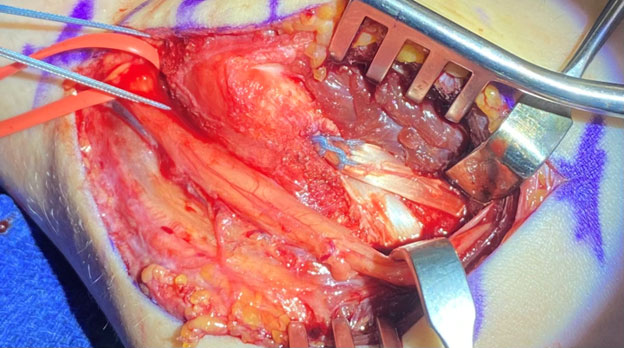

- However, there is increased interest that partial-thickness or acute full-thickness tears in an otherwise healthy ligaments are candidates for a direct repair of the UCL

- Theoretical advantages to repair over reconstruction include a much shorter postoperative recovery and return-to-play time

- Patient selection is perhaps the most important factor determining outcomes for repair. Acute partial thickness or full-thickness tears with otherwise healthy ligament are ideal candidates. The final decision to perform a repair is typically an intraoperative decision after inspection of the quality and integrity of the ligament.

- Patient with poor tissue quality due to attenuation or chronic tearing or ligaments with bony ossicles are not great candidates for a repair

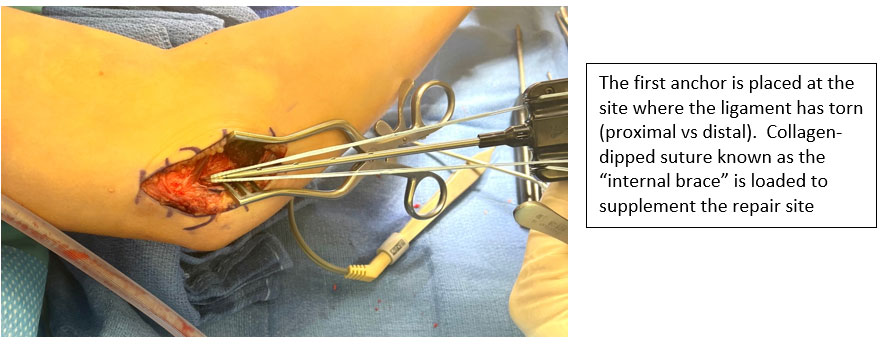

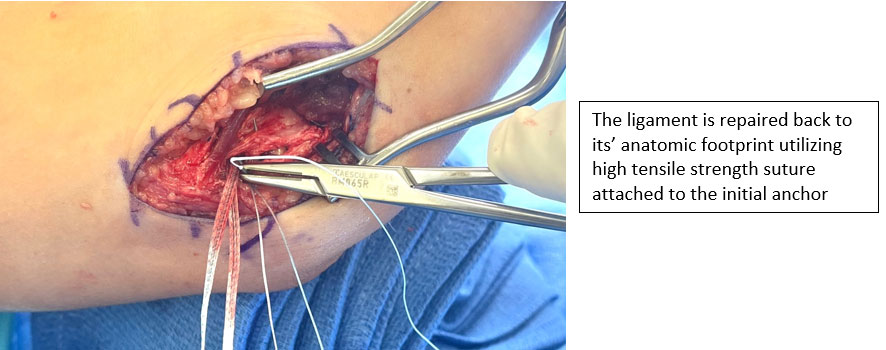

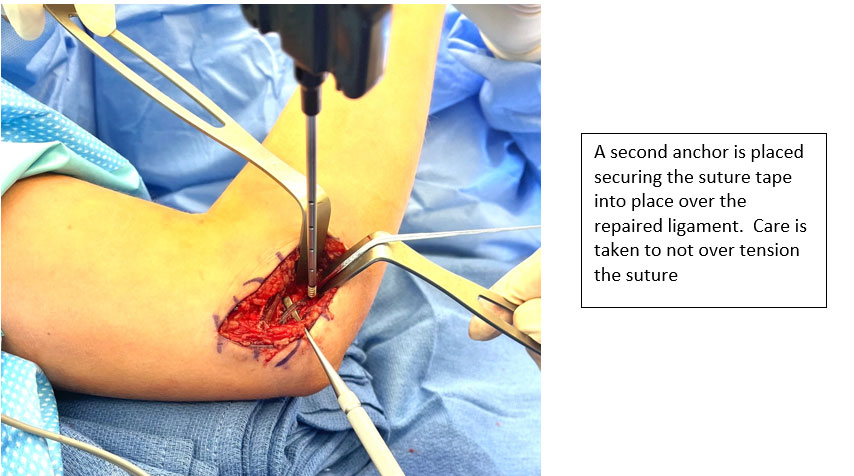

- Repair is typically performed using a combination of suture anchors augmented with a collagen-dipped suture to restore the ligament to its native anatomic footprint

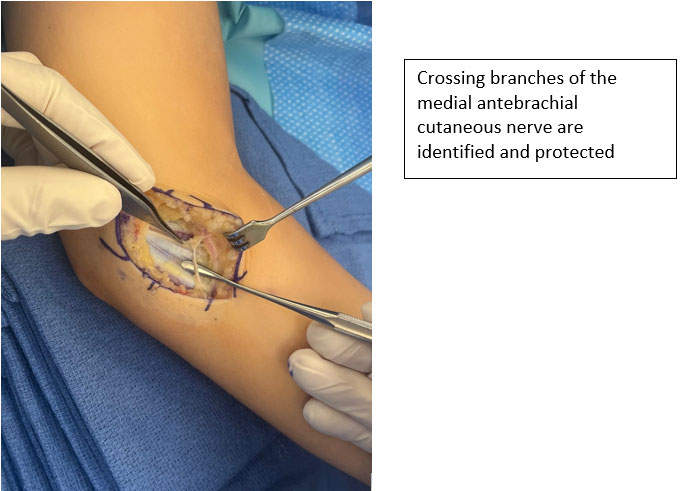

Medial approach to elbow is utilized

A muscle splitting approach is utilized to expose the ulnar collateral ligament (red arrow)

The ligament is incised, and a proximal avulsion of the ligament is identified

POSTOPERATIVE REHABILIATION:

- UCL reconstruction was historically a career-ending injury. However, current surgical techniques have led to high rates of return to throwing and athletic activities.

- Outcomes and return to sport following Tommy John UCL reconstructive surgery depend on precise recreation of the UCL anatomy at the time of surgery and diligent postoperative rehabilitation

- Significantly worse outcomes are associated with revision reconstruction

- Postoperative rehabilitation consists of early active protective wrist, elbow and shoulder range of motion while giving the ligament ample amount of time to heal.

- Perhaps the most crucial component to a reliable outcome is the appropriate postoperative therapy. It is important that athletes recover under the direct guidance of a therapist who is familiar and experienced with postoperative protocols for UCL reconstruction and repair. They will help develop a personalized rehabilitation program for each athlete.

- The weeks and months following surgery should follow specific protocols to help restore motion, strengthen the shoulder, core and structures around the elbow. A certified physical therapist with experience in throwing athletes will be able to guide the athlete towards an appropriate pre-throwing testing and through an interval throwing program. Any deviation in these protocols can lead to reinjury or a prolonged postoperative recovery.

UCL Reconstruction Postoperative Protocol

You will need the Adobe Reader to view and print these documents.